Prevent cancer cells from colonizing the liver

Researchers at ETH Zurich have discovered how colon cancer cells become established in the liver. Their findings could open up new ways of suppressing this in the future.

When cancers end fatally, in nine out of ten cases metastases are to blame: offshoots of the so-called primary tumor that affect other organs in the body. While medicine has made great progress in the treatment of primary tumors, it is still largely powerless when it comes to metastases. There are currently no drugs that can prevent new metastases.

Now the trade journal external pageNature The results published by researchers led by Andreas Moor at the Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering at ETH Zurich in Basel show how colorectal cancer cells colonize the liver. Their findings help to develop a possible treatment that may prevent the formation of metastases in the future.

Molecular docking mechanism broken down

In order to form new offshoots, cancer cells detach from the initial tumor and enter the blood vessels. "The fact that bowel cancer spreads to the liver has to do with our blood supply," says Moor. The blood first accumulates nutrients in the intestine, then it goes to the liver, where the nutrients are metabolized. The liver is the final destination for the spreading bowel cancer cells. "They get caught in the capillary network of the liver," says Moor.

As Costanza Borrelli, a doctoral student in Moor's group, and her colleagues have now shown, it also depends to a large extent on the liver cells whether the cancer cells that have stuck around can gain a foothold in their new location. Scientists have known for over 100 years that cancer cells - like plant seeds in the soil - are dependent on their environment for their growth. However, the molecular mechanisms that play a role in this have been a mystery until now.

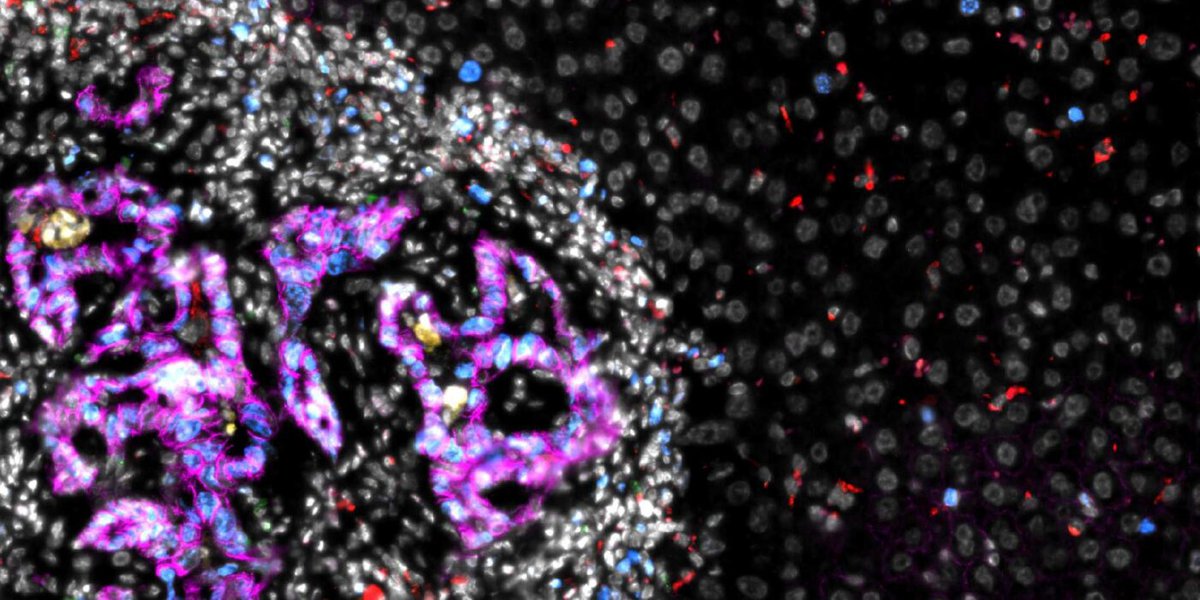

Using sophisticated experiments on genetically modified mice, Moor and his team have discovered that it depends on certain proteins on the cell surface: if liver cells have a protein called plexin B2 and the colon cancer cells have certain proteins of the semaphorin family, the colon cancer cells can dock onto the liver cells.

Signposts in the nervous system

The fact that cancer cells that display semaphorins on their surface are particularly dangerous is confirmed by clinical studies to which Moor's researchers refer in the article. The study data show that liver metastases develop earlier and more frequently in colorectal cancer patients if their tumor produces large quantities of semaphorin.

Plexin - and its interaction partner semaphorin - were previously known to researchers for their function in the nervous system, where the two proteins guide the growing projections of nerve cells and thus ensure their correct interconnection. "Why liver cells also form plexin and what this protein does in the healthy liver is completely unclear - and we are very interested," says Moor. The question of its function therefore remains unanswered.

Back to the sedentary form

However, Moor's researchers have clarified that the direct contact between plexin and semaphorin triggers profound changes in the colon cancer cells. In order to break out of the initial tumor, the cancer cells have to change their identity: they lose their affiliation to the covering layer in the intestine, the so-called epithelium, and cut the close connections to their neighboring cells.

On their way in the bloodstream, the cancer cells then resemble cells from the connective tissue (the so-called mesenchyme). However, when they find their new niche - thanks to the plexin on some liver cells - the cancer cells develop back into a sedentary form: "Epithelialization takes place," the researchers write. "You can see this immediately in the cancer cells, because they form invaginations that resemble the folds or crypts in the intestine," says Moor.

Sensitive time window

The discovery is not only likely to be of significance for colorectal cancer patients, as the researchers have shown in further experiments that plexin also promotes the development of new offshoots in melanoma and pancreatic cancer. Many new research questions arise for Moor and his team. One of them is that when cancer cells grow into a tumor, they also influence the cells in the surrounding area. "Cancer cells build their own ecosystem," says Moor.

If it is possible to prevent the interaction between plexin and semaphorin, which is crucial for implantation, it may be possible to prevent the cancer from spreading new offshoots right from the start. Because right at the beginning, when the relationships between the cells in this ecosystem are not yet established and well-rehearsed, tumor offshoots are particularly vulnerable, says Moor. When he speaks of a "sensitive time window in the development of metastases", he seems confident, even if the road to a possible treatment is still long.

Source: ETH