Automated driving: Opportunities and risks

Automated driving is revolutionizing road traffic. Assistance and automation systems are intended to increase safety and comfort - but they also bring new challenges. And the question: how much trust and responsibility can we leave to the systems?

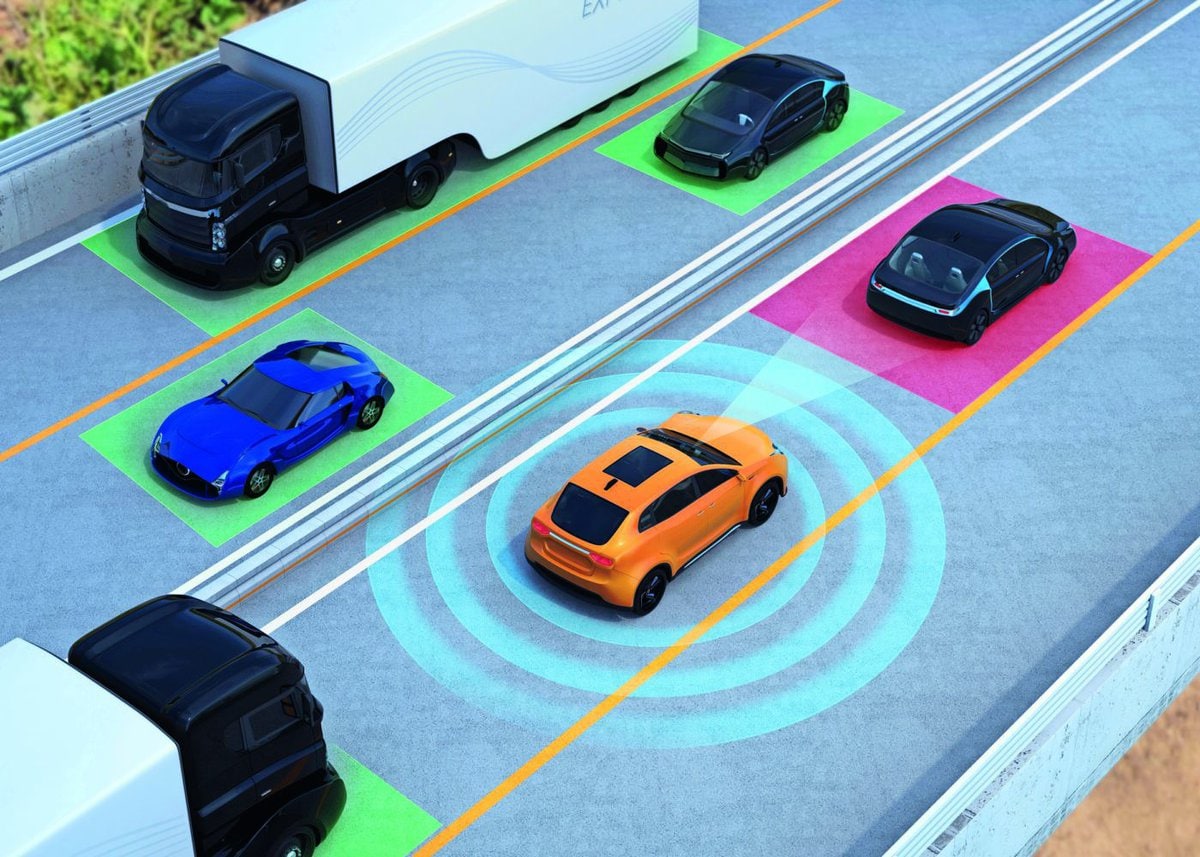

Automated driving will fundamentally change road traffic. Numerous driver assistance systems (DAS) are already in use today. Systems such as emergency brake assistants, emergency lane departure warning systems and blind spot warning systems are becoming increasingly widespread and are already a legal requirement for all new vehicles in Switzerland. Their preventive benefits are scientifically proven. The BFU explicitly emphasizes the high preventive benefit in its prevention portal Sinus plus (sinus-plus.ch): "Active safety technology in vehicles has a high prevention potential. It warns or intervenes in dangerous situations and can thus prevent accidents".

New requirements for road users

At the same time, systems that provide permanent assistance with steering, braking and acceleration (automation level 2) or even take over these tasks completely at times (automation level 3) are becoming increasingly important. Such "level 3 automation vehicles" primarily ensure greater driving comfort, for example on long highway journeys. However, they also place new demands on road users, particularly in terms of understanding the system, continuously understanding the current traffic situation and being ready to take over at any time.

As these technologies continue to develop, the need for clear rules is also increasing. Switzerland took an important step in this regard in 2025 with the Ordinance on Automated Driving: vehicles with a takeover function may be used on freeways under certain conditions - for the first time, it is permitted to take your hands off the wheel temporarily. These developments bring new opportunities - but also new challenges. For example, due to excessive trust in the systems, declining vigilance and the difficulty of reacting appropriately at critical moments.

This article deliberately focuses on level 3, in which the driving task is partially taken over. It is the most safety-relevant transitional form between manual driving and full automation, in which technical, legal and human requirements are particularly concentrated.

What is allowed - and what is not (yet)?

On the one hand, the technology opens up new opportunities for innovation in the mobility sector and creates comfort and relief for drivers. On the other hand, it raises practical and legal questions, particularly with regard to the permissible performance of so-called non-driving activities.

The key question is: What is permitted while the driving task is being carried out automatically by the vehicle? This question currently remains unanswered in the regulation - it leaves open which specific actions are permitted.

Balancing act for non-driving activities

This regulatory reluctance is understandable and reflects the current state of the art: automated vehicles are currently not able to guarantee sufficiently long time windows for a safe take-back in the event of intensive distraction. However, such predictive functions would be necessary in order to hand over responsibility in a controlled and more concretely defined regulatory manner and to actually give users more freedom of action.

For drivers, this creates new uncertainties in dealing with such systems and a safety-related dilemma. The uncertainty: They lack prospective orientation. They cannot know with certainty from the outset what actions are permitted. In the event of an incident, a court will decide on the appropriateness of the non-driving activities carried out.

The dilemma: on the one hand, they are formally released from the duty to monitor and are allowed to engage in non-driving activities within the framework of the regulations, but risk not being able to intervene in time in an emergency. It is difficult to assess the extent to which an activity impairs the ability to react. Nevertheless, drivers must constantly assess what they are "capable of" in a specific situation - and run the risk of overestimating their own ability.

"The developments bring new opportunities - but also new challenges. For example, excessive trust in the systems, declining vigilance and the difficulty of reacting appropriately at critical moments."

Dealing with non-driving activities thus becomes a balancing act: What is still unproblematic, what is already risky? Where to put your hands - except in your lap? The existing lack of clarity makes it difficult to handle the technology in a safe and standardized manner.

How these uncertainties can be dealt with in practice will become clear with increasing experience - and ultimately through the first precedents in case law. Until then, the following applies: anyone who drives level 3 in the future will officially be allowed to do little - and will drive most safely if he or she does not engage in any non-driving activities.

Driver training as a supplementary component for safe system use

Technology alone does not make traffic safer. Its effect only unfolds in conjunction with competent, well-trained drivers - especially when using vehicles with automation systems. Driver training plays a central role in this. Although vehicle drivers have to do less and less actively, there are more and more and no less demanding requirements - for example with regard to understanding what their own vehicle can actually do and where its limits are. A realistic self-assessment and a situationally appropriate reaction are also challenges. Is driver training as we know it still at all suitable for this?

Driver assistance and automation systems have been a mandatory part of training since July 2025. Future drivers should not only learn how to operate the systems, but also when and why they should not blindly trust them. The aim must be to convey a realistic understanding of the possibilities and limitations of the technology - and to strengthen the ability to act safely and responsibly.

In the long term, it will also be important to sensitize experienced drivers to these changes - for example through practical training courses. Only if all road users are sufficiently familiar with the new technologies and use them competently can the potential of automation actually be exploited - and in such a way that comfort gains do not come at the expense of road safety.

And then we drive without a guide

Driverless vehicles (automation level 4) take over the driving task completely, but only on cantonally authorized routes. They are already operating in pilot projects in Switzerland. In contrast to level 3, there is no longer a human fallback level. This significantly increases the requirements for system reliability, well-developed infrastructure and social acceptance.

In the future, such systems will primarily be used in the context of commercial mobility services - for example in public transport or logistics. For the time being, automation level 4 seems less relevant for private individual transport, not least due to the high technical and economic costs involved. However, new business models - such as driverless sharing fleets - could lead to the first applications also emerging in motorized private transport.

The role that humans will play in automated traffic in the future depends largely on the extent to which automated systems can be designed in a technically reliable manner, legally classified and at the same time safely integrated into real traffic contexts.