Good bacteria for bad wounds

Empa researchers are developing a dressing with lactic acid bacteria. The probiotic lactobacilli are intended to promote the healing of chronic germ-loaded wounds by destroying stubborn biofilms.

Millimeter by millimeter, new tissue makes its way through a wound until it has closed a skin lesion again. Soon, in the best case, there is nothing left to see of a knee scrape, a finger cut or a burn blister. Not so, however, with chronic wounds: If the injury has not closed after four weeks, there is a wound healing disorder. Sometimes, seemingly harmless tissue damage can develop into a permanent health problem or even blood poisoning. Treatment is particularly difficult because germs settle in these chronic wounds and know how to protect themselves perfectly. These bacteria form a biofilm, a stubborn compound of various pathogens. For their own protection, they produce a layer of mucus with which they attach themselves to surfaces. Antibiotics or disinfectants reach their limits because they cannot reach the dangerous germs.

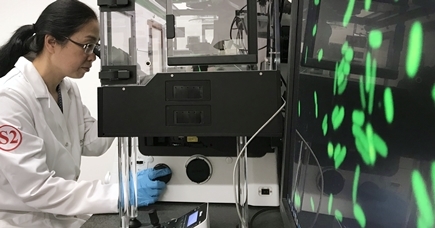

A team from Empa and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston is currently developing a wound dressing that uses "good" probiotic bacteria to combat biofilm inhabitants. The researchers recently published a proof of concept in the journal Microbes and Infection.

The team led by Empa researchers Qun Ren and Zhihao Li from the "Biointerfaces" laboratory in St. Gallen used living lactic acid bacteria for the new dressing. These probiotic lactobacilli include some good acquaintances of humans: As beneficial organisms, for example, they are found in healthy intestinal flora and play a major role in the production of foods such as yogurt and cheese. "Lactobacilli are biocompatible and create an acidic environment by producing lactic acid," says physician Zhihao Li, who contributed clinical expertise to the project as a visiting scientist at Empa. This should push the unfavorable, basic pH value in chronic wounds in the right, i.e. acidic, direction, he says. "In our laboratory experiments, the bacteria were able to produce a strongly acidic pH of 4 in the culture medium," said team leader Qun Ren. Thanks to lactic acid production, it was also possible to attract desirable cells that contribute to wound healing under laboratory conditions.

Beneficial association

Finally, the beneficial organisms were integrated into a wound dressing that protects chronic wounds from further infections. This simultaneously enabled the living lactobacilli to produce lactic acid in a protected environment. As desired, the dressing released the acidic product into the environment in a controlled and steady manner. In laboratory tests, the material with integrated lactic acid bacteria was able to completely destroy a typical biofilm of pathogens in a culture dish. The question was now: Do the beneficial organisms also pass the test with human skin?

In small tissue samples, the researchers created artificial wounds two millimeters long and allowed a biofilm with the wound germ Pseudomonas aeruginosa to grow. In this three-dimensional model of a human skin wound, the probiotic wound dressing was to prove its worth. And indeed, the bio dressing reduced the number of pathogens by 99.999 percent. In addition, the researchers were able to demonstrate that the probiotics are well tolerated by human skin cells and at the same time trigger the production of messenger substances of the immune system. Following this "proof of concept", further analyses of the mechanism of action should help to exploit the potential of the beneficial organisms from the bacterial world for a "living" wound healing material.